I’ve had marriage on the brain lately. I mean, duh, because I’m in one, and have been for almost 15 years now, but also because I’ve been reading a lot about them. If you follow me on Instagram you’ve seen me posting selfies with Kimberly Harrington’s excellent “But You Seemed So Happy,” which is a collection of essays about her amicable (and seemingly mutually beneficial) divorce. I’m also in the middle of “Foreverland: On The Divine Tedium of Marriage” by the great Heather Havrilesky and “Mating in Captivity” by Esther Perel, who’s got the one-two punch of a therapist’s deep understanding of erotic intelligence and the sexiest accent an audiobook could ever hope for. If this trio sounds like a swan dive into self-help land, so be it. But if you’ve stumbled across any of my oversharing online writing, or read my memoir “Unabrow,” you probably already know that my own marriage has been a bit of a roller coaster—the kind that sort of makes you nauseous but that you can’t help getting back on again and again.

My (sweet, patient, fundamentally good but also human and therefore fellow hot mess) husband Jeff and I have been in and out of couples counseling for years now, hashing out some personality and communication differences that we have spent the better part of two decades trying to reconcile, and which I have written about fairly candidly, once even in print in the New York Times (sorry Jeff—but you bought this cow, babe). I like to be open about my marriage, and read about other people in less-than-perfect unions because I feel that, as a culture, Americans don’t tolerate much gray area when it comes to our representations of long-term love. Despite the slow trickle of more non-traditional relationships in mainstream media, the heteronormative fairy-tale model of romantic love still reigns supreme, and our collective baby steps of progress on this front haven’t been enough to finally topple the desperate, culturally-mandated scavenger hunt for “The One” that makes dating feel like an ever-so-slightly hornier but no less dangerous version of the Hunger Games.

It’s hard to be in a serious relationship for more than a few years and not sometimes wonder if you’re doing it wrong. I think for me, the “happy ending” shit really wormed its way into my brain at a tender age and took root. It’s taken me an embarrassingly long time to start to question some of the beliefs I had about what a successful relationship looks like. I was a full-grown adult before it even occurred to me that the majority of fairy tales (and rom-coms, and installments of delicious reality trash like Love is Blind) end at the beginning of a love story. Which is not at all helpful, because the beginnings are supposed to be great. It’s the endless, confusing middles where we get stuck. And unless we’re newly in love or at death’s door, we’re all fucking stuck in the middle with the person we picked to stagger through life with, just like Stealers Wheel told us.

So, I guess, this is going to be a semi-organized rant about love. Romantic love, to be more specific—lust and passion and long-term relationships with at least the occasional promise of nudity—not friendships or self-love or emotional attachments to small animals/children, or the awkward bond I share with the septuagenarian who runs the corner liquor store. I’ve spent over half my life trying to navigate the disorienting divide between the expectations set by the models of fictional love we hold up as “real” and my own true, lived experience of falling in and out of lust, love, obsession, and committed companionship (I cannot overstate the cavernous emotional gap between watching Billy Crystal literally sprint through the streets to tell Meg Ryan he loved her in When Harry Met Sally, and having my college boyfriend hand me a CD-ROM of Mavis Beacon Teaches Typing right after dumping me).

I lean hopeless romantic, but even the most cynical among us are vulnerable to the incessant, repetitive messages we get through the love stories we ingest… whether it’s high-minded BBC stuff like the emotionally unavailable Mr. Darcy stepping sensually out of a lake, or the corn syrup courtship of a show like The Bachelor, but how does any of that actually help us during the confusing, scary, emotionally messy process of choosing a life partner when we aren’t living in a 19th century comedy of manners in the English countryside, or being held captive with two dozen pharmaceutical sales reps at a Sandals Jamaica? In this essay I will—

Just kidding. This is a free Substack and I’m gonna wing it. Hold onto your butts.

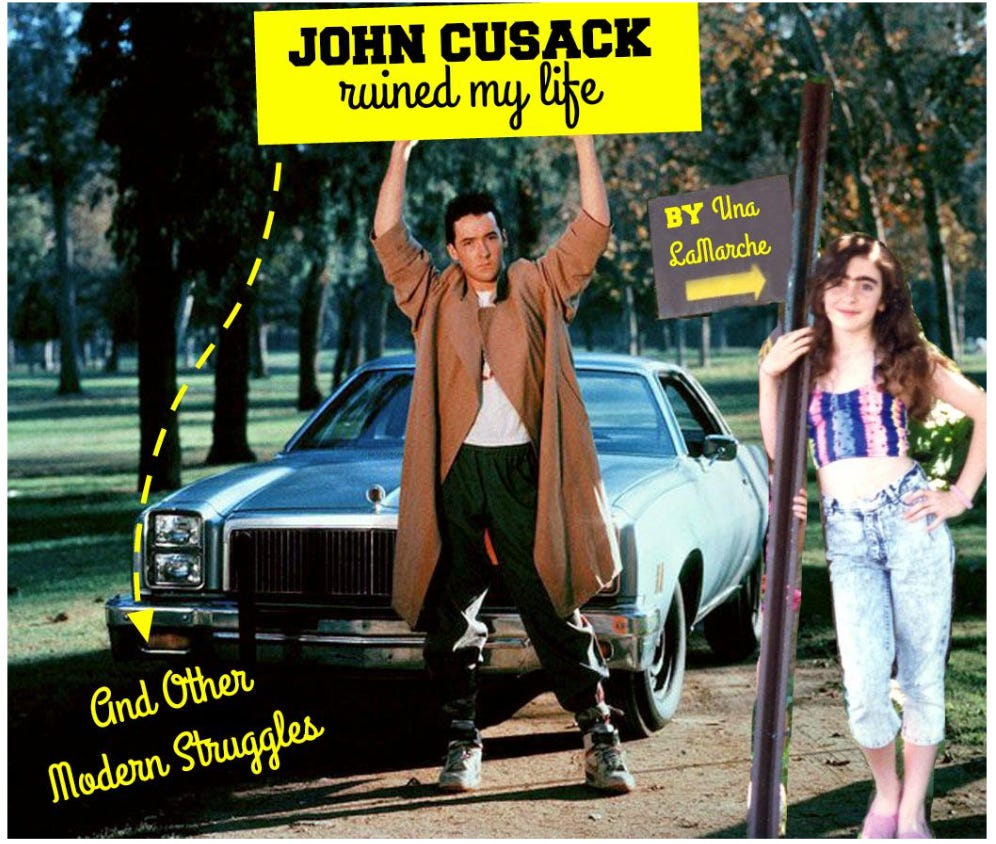

In the beginning, there was Lloyd Dobler.

Say Anything came out the day after my ninth birthday. My parents didn’t let me see it in theaters, because: A) they were responsible adults who intuited that their daughter, who routinely slept in a pioneer-era floor-length nightgown and had a May-December crush on Rick Moranis, might not be ready for a movie about teenage sexual awakening; and B) I was much more excited about seeing Troop Beverly Hills.

So I did not watch in real time as John Cusack hoisted that iconic boombox over his head, releasing both the tender ache of longing and the breathy vocals of Peter Gabriel on an unsuspecting world. I did not, as I blithely continued my sheltered third-grade existence, realize that the image of 23 year-old Cusack standing in a trench coat in front of a blue Chevy Malibu would soon be seared into my developing brain, setting me up for a lifetime of romantic disappointment long before I could even fill a training bra.

OK, fine, it wasn’t all his fault. But he was my gateway drug. Despite Public Enemy’s assertion that 1989 was just “the number, another summer,” it was a cultural last gasp of sorts, ushering out the decade of hair metal and John Hughes for a confusing new era that simultaneously witnessed the rise of riot grrls and the rebirth of the classic romantic comedy, in which any woman able to successfully pull off a layered bob was instantly rewarded with a dreamy, adversarial soulmate and a wacky, overalls-clad best friend. I spent the next ten years of my life consuming as much media as possible, internalizing the misleading message that each of us has a soul twin, and that it is our sacred quest to find them, whoever and wherever they may be, preferably by the age of 30, and especially if we have ovaries. Instead of having my own romances, I watched them play out on screen. By the time I did start dating in college, I was too far gone to be saved.

It did not help that my first real boyfriend was straight out of central casting for The One. Teen idol handsome, hot bod, killer smile, good heart. I stood no chance. I met him during rehearsals for a musical where we both played teenage runaways: he, a heroin dealer in a leather jacket; I, a gender-ambiguous street urchin with fake dirt on my face and my long, dark hair tucked up inside a ski cap.

His name was Wesley, like Cary Elwes in The Princess Bride, and he looked like someone who would get stopped on the street and asked to play a Disney prince on a cruise. I was instantly smitten, and seduced him during the cast party by wearing snakeskin-print Mudd brand pleather pants and (reportedly) doing body shots off of his neck. I fell in love with him like falling off a cliff. It was, as Zoe Kazan perfectly describes it, “the real thing, the full symphony.” Having never felt anything like this insane, all-consuming flood of dopamine before, I believed, at 20 years old, that I was one and done. We talked about getting married and having kids before we’d been dating six months. Over the summer, I surprised him with a visit to Boston, where he was staying with his sister, and accidentally set his bedroom on fire by leaving a curtain resting on a halogen lamp. Did I mention it was also his birthday? He loved me so much that he laughed when I told him. Our romantic comedy was exactly what I always dreamed it would be (drug-addicted runaways: classic meet-cute!). Until, all of a sudden, it wasn’t.

There was nothing special about our breakup, not really. No inciting incident or dramatic betrayal. We just slowly, painfully realized we weren’t going to make it. We started getting on each other’s nerves, having fights. We were each having separate identity crises that made us anxious and insecure. We loved each other madly but it wasn’t enough. We’d done all of the things I thought were signs of true love: we made out in the rain, we wrote feverish love letters, we clung to each other in our XL twin dorm beds… I mean, he was even in an a cappella group, for Christ’s sake! On Valentine’s Day, 2002, he had them all serenade me in the campus quad. Still, he broke up with me less than two weeks later, which cruelly coincided with our one-year anniversary. I remember crying and protesting, “But I don’t want to have sex with anyone else!” (He was the second person I’d ever slept with.) Yet he dumped me anyway and I was left to listen to Des’ree’s “You Gotta Be” on repeat and abuse the remainder of my recent wisdom tooth-removal Vicodin prescription, lying on the couch wailing, “but he was The One!” to my four roommates, who were just trying to focus on Ally McBeal.

Wes broke up with me in February 2002 and I started dating Jeff in April 2003, which gave me exactly 14 months—although I didn’t know it then—to sow my oats. In that time, I entered into an extremely ill-advised love triangle when I started dating the guy one of my friends had a long-standing crush on (~3 months), showered with a frat boy I was not even attracted to (1 night), succumbed to the charms of an upperclassman who pursued me with determination only to be a dick once we slept together (~2 months), had my one and only same-sex hookup (1 night), and slept with a platonic roommate mainly because we were bored (2 nights). Including my husband, I have never had sex or fallen in love with anyone who did not attend my small liberal arts college. But again, I wasn’t looking to rack up notches on my bedpost. If anything, my extremely brief, milquetoast attempt at promiscuity was just an extended rebound. I was looking for that high of love and validation that I’d lost, in any form I could get it. I was never interested in casual sex, even if I pretended to be. I wanted love with a capital L, with googly eyes and songbirds and jazz hands. I wanted love like in the movies. I didn’t know any better.

It’s probably obvious by now that I don’t really believe in soulmates. I think two people can be extremely compatible, and balance out each other’s specific brand of neuroses in ideal ways. I know that there are couples out there—probably a lot of them—who truly believe that there is no other person they could ever be happy with. I’m not here to argue with you if you’re one of those people. I’m jealous if you are. But I think the myth of The One does more harm than good for most of us. It implies that life is a multiple choice test with only one correct answer, a punishing bubble sheet of existence that will be merciless if you choose wrong, or get #2 pencil marks outside the lines. There are some things that come down to true or false, right or wrong, A or B. Math and science come to mind. I’m not saying there are no immutable facts in the world. But I see love as more of a persuasive essay. It’s opinion, mixed with emotion and conviction (don’t forget delusion!). It’s graded on a curve. Also, the math of The One just doesn’t work out. In a world of almost 8 billion, what are the chances that your One lives in the same country as you do? And falls in an appropriate age range? And isn’t already married or committed to someone else? I may be a magical thinker, but I recognize confirmation bias when I see it. The two people I have been in love with both attended the same small-town university at the same time as me, as part of a student body of about 3,000 people between the ages of 18 and 22. That’s not fate. That’s proximity.

That said, I did not actually fall in love with Jeff at college. I was vaguely aware of him, and we hung out in the same circles, passing each other in the cloud of pot smoke at our senior house parties. He was also my Acting T.A. junior year, which is important to know because I am a terrible actress, and so he saw one of my most glaring flaws immediately. But it wasn’t until a year after graduation that we found our way into the same Argentinean tango class, held in a dingy studio above a natural food store on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. It was, in retrospect, a pretty cinematic origin story: Jeff is not the kind of person who would normally take a dance class, but it was taught by his roommate—a mutual friend of ours from college—who was trying to make extra money, and so we both trudged up the steep staircase once a week and glided across the parquet floor in socks, changing partners and exchanging glances, until one night… we were the only two students who showed up. We spent an hour tangoing and then went out for beers afterwards, trading stories about the tragic states of our love lives. At some point that night, something quietly but unmistakably sparked between us.

The next week, we met at another bar near the Bowery, and afterwards he insisted on walking me home to Brooklyn across the Manhattan Bridge. We actually tangoed on the bridge. At 2 a.m. Even Cameron Crowe would have puked. We finally kissed, a few days later, by sharing a stick of gum, Lady and the Tramp style (although to be fair we were much more drunk than those dogs seemed). We immediately had clandestine sex in the same house where my parents slept (unavoidable as I was living at home at the time), started dating, fell in love, got married, had kids, and lived happily every after. Bahahahahahahaha. JK. That’s how the movie would end. But in life, there are like 50 more years you have to slog through before the credits actually roll. And after a few years Jeff’s and my movie started looking a lot less like a rom-com and more like a true crime documentary. I mean look at this photo and tell me you can’t picture him pushing me off a boat:

I want to acknowledge up front, since I deeply fear the judgment of others even while I share my innermost thoughts and feelings on Beyoncé’s internet, that my marriage is not representative of all marriages. If I have learned anything from being in a committed relationship for almost 20 years, it is that there are an infinite number of qualities that draw two people together, and that predicting long-term compatibility based on initial attraction is a fool’s game. For example, what first attracted me to Jeff was his dark, depressive, enigmatic personality. “I can fix him with my love!” I thought, upon waking to discover that he had left my bed in the middle of the night and split without so much as leaving a note (and possibly taking some money). That seems like an obvious red flag now, but hey—we’ve made it this far. When I asked Jeff what initially drew him to me, he said, and I quote, “your boobs in that shirt.” I instantly knew the day and shirt he was referring to, as I had opted not to wear a bra. And the fact that he picked me based on my tits is even more impressive given that I have long worried they are below average! See? There’s no algorithm at play here--it’s all chaos, babies. Good luck.

But I can’t be alone in looking back on my relationship and wondering if I somehow missed the time of death for whatever black magic made us fall in love in the first place all those years ago. Because while time builds trust and familiarity and the kind of unselfconscious comfort that leads you to not even flinch when your partner complains about their diarrhea, or canker sore, or stye, or plantar wart (or whatever other unholy physical ailment you’ve already made a public vow not to leave them over), time and passion are usually inversely proportional. Which is why I am so suspicious of people who seem to still be deeply in love. Or, even worse, who claim to be “best friends.”

Come Valentine’s Day (or Mother’s Day, or Father’s Day), you can’t scroll Instagram for more than a few minutes without seeing someone refer to their spouse or partner as their “best friend.” Usually it’s part of a longer list of titles. Sample caption: “Happy [insert occasion] to my best friend, my soulmate, my confidant, my partner in crime. I couldn’t do life without you. You’re my everything!” CUT TO: Me rolling my eyes so far back in my head I can see into my Inside Out-style brain HQ, which is filled with bitchy Winona Ryders from the scene in Reality Bites when she’s chain-smoking and calling the psychic network.

[Deep breath.]

I realize this makes me seem bitter. If your spouse or partner of many years (NOTE: if you have only been together a few years, or—bless your heart—are still in the early months of dating, this is not directed at you and I hope you’ll revisit this a decade down the line to find out that I am PSYCHIC!) is truly your best friend in this world, that is a beautiful thing. But I suspect that for most people, it is bullshit. Now, pitchforks down; I am not arguing that you should not be friends with the person you choose to share a home, a bed, possibly dependent children and/or pets, and a manure trough’s capacity of responsibility with. Friendship, while not required, can be a fantastic foundation for love—and of course the longer you spend with someone the better you get to know them, which means that over time, every romantic relationship will become as familiar as a longterm friendship (which is not the same thing as being best friends, in my opinion).

I just think that in combining two of life’s greatest and richest relationships—the best friend, and the romantic partner—we are putting way too much pressure on one person… not to mention stress-testing our ability to love that one person in all the ways that the overlap of a BFF/lover Venn diagram requires. If your partner is your best friend, who do you complain about them to? When you’re sick of looking at their dumb face, or watching them load the dishwasher wrong, or waiting for them to undergo a sudden and dramatic personality shift that will fix everything in one fell swoop, who do you go our for drinks with to escape them? Are you never supposed to get sick of looking at their dumb face? Are you never supposed to crave escape? If so, I have made a terrible mistake.

At our wedding in 2007, Jeff and I wrote our own vows. They were funny and light and whimsical (Sample line: “I promise to laugh with you often, and at you sometimes”) and seemed perfect for the occasion. Most wedding readings and vows tend to be full of almost ridiculous levels of faith and hope. It’s honestly kind of hard to listen to them as a longtime married person now. “Ha ha, good luck, you dumb babies,” I think to myself, clapping as they do the recessional and I look for the nearest cocktail tray. Don’t get me wrong—I still love weddings. But you can’t seriously know what you’re vowing to when you’re still so high on the endorphins of romance. You can promise anything in your wedding vows and feel confident you’re speaking some sort of divine truth. Like remember in Braveheart when William Wallace tells Murron “I will love you my whole life; you and no other”? And then she immediately dies so he never has to follow through, or love her when she’s not a hot young thing but a hunched middle-aged shrew asking him when he’s going to start putting his mead bottles in the recycling bin instead of leaving them on the kitchen counter which is literally eight inches away from said recycling bin? That’s what I’m talking about. There’s no excuse for the kinds of beer goggles we intentionally strap on for wedding vows, even when we’re shelling out 50K for tiny empanadas and a Motown cover band.

What I’m getting at is that lifelong commitment is hard, even under the best of circumstances. (In retrospect I think the hora was trying to prepare me for this fact, as I struggled in vain to hold onto a chair with no arms, hovering eight feet over a drunken mob.) And Jeff and I don’t usually have the best of circumstances, global pandemic and looming world war notwithstanding.

The past decade has been pretty rough. Co-parenting is a constant, humbling struggle, money is tight, quality time is scarce, and stress is high. It’s a recipe for resentment, and for forgetting why you liked each other enough in the first place to fund an extravagant, legally binding party just to rub it in people’s faces.

I don’t think we actually uttered the words “for better or for worse” in our vows, but everyone knows that’s the deal you make, before you step on the glass or jump the broom or almost fall to your death from your hora chair. And while we’re lucky beyond belief in many ways, we’ve been wading towards the worse end of the spectrum for a while. Which is why I feel compelled to write this. Because while bliss in any marriage is ideal, and divorce—or something worse, like the end of Fatal Attraction—is less ideal, I think most relationships hover in between Tom Hanks-Meg Ryan soulmate land and Michael Douglas-Glenn Close bathtub murder. And we should normalize it!

We should normalize admitting how much it sucks that passion fades. I get why it happens—our brains can’t handle that much dopamine long-term; we would never get anything done if that new-romance high lasted more than a few years. But still, it sucks! It fucking sucks!

We should normalize the bone-crushing weight of parenting, and how a child can change a relationship in ways you don’t expect. A baby is literally the manifestation of love (or, OK, at least lust) between two people, so it seems logical that it would multiply affection instead of divide it. But parenting is hard, sleep deprivation is real, and sometimes, at the end of the day, you only have enough love left for one person (and the kid always wins).

We should normalize how every couple is cosmically destined to have the same fight over and over again, at least once a month, for the rest of eternity, like a really terrible remake of Groundhog Day where the suspense comes from what will die first: your marriage or one of you?

We should normalize that love is rarely patient, and not always kind (side-eye, Corinthians). That love always means having to say—and usually YELL—you’re sorry. That there’s magic in falling in love, sure, but that the real trick is keeping it going. That love grows but also fades over time, and that those two things are not mutually exclusive. That people can love each other and get divorced, or hate each other but stay married, and that length is not always the tell of a successful love story (girth, as always, is more important.)

Finally, I demand the production of a mockumentary about iconic fictional lovers and where they would realistically be twenty years after the end credits of their romantic comedies rolled. ‘Cause I can guaran-fuckin’-tee you that if Murron had lived, she wouldn’t be getting under that kilt on the regular.

All joking aside, it would be irresponsible of me not to say outright that some relationships need to end. There are so many ways that a marriage or longterm partnership can be toxic, abusive, or simply unhappy enough that it’s causing serious pain to the people in and around it. In those situations, you should not settle for what you have. But what if you find yourself in middle age, having reached all the Game of Life milestones—a partner, maybe some kids, a house, a career—and discover, that after all of that build-up and searching and trying that after ten or twenty years your relationship is just… okay? What if it’s not transcendent or awful but has just nestled itself into a gentle, undramatic rut that could last forever unless one of you makes the effort to change it? And you know each other well enough by now—especially after all of that diarrhea—that you know neither one of you has the energy to find the remote, let alone go on an Indiana Jones-style quest to find the spark of passion again? What then?

The writer and advice columnist Heather Havrilesky published an excerpt from her memoir Foreverland: On The Divine Tedium of Marriage, in The New York Times this past December. Her marriage sounds a lot like mine—happy-ish, but far from perfect, and powered by the twin engines of passion and resentment that come with hitching yourself to someone you have both fiery chemistry and vast personality differences with. So it makes sense that I deeply related to the following passage:

“Do I hate my husband? Oh for sure, yes, definitely. I don’t know anyone who’s been married more than seven years who flinches at this concept. A spouse is a blessing and a curse wrapped into one. How could it be otherwise? How is hatred not the natural outcome of sleeping so close to another human for years?”

—“Marriage Requires Amnesia,” The New York Times, 12/24/21

But WOW, a lot of other people did not like that. Readers of the excerpt got up in arms. How dare a woman suggest she sometimes felt deep loathing towards a man she herself (!) chose (!!) to spend life with?! How sad for him that he was shackled to such a joyless shrew! How tragic that she did not understand that the first rule of marital fight club is that we do not, under any circumstances, talk about marital fight club!?! Multiple news outlets covered her confession. A woman saying she sometimes hated her husband? That was breaking news!

I don’t think the readers who attacked Heather Havrilesky for her admission are necessarily aware of why they had such a visceral, negative reaction. After all, this was a personal essay excerpted from one woman’s memoir, clearly not meant to be taken as a blanket statement about the institution of marriage. But I think that the reaction to her piece reveals a deep-seated devotion to the black-and-white binary we’ve been sold about love, among so many other, often much more important things. Our change-averse culture has always been inhospitable to people who don’t conform to binaries. Are you a boy, or a girl? Gay, or straight? Good, or evil? A madonna, or a whore? A Democrat, or a Republican? Choose a side, pick a lane, and don’t make anyone think too hard about that vast, murky middle we’re all floating in, whether we know it or not.

So, while it’s usually not life or death (except for Glenn Close, or Romeo & Juliet, or Jack on the raft, or Ali MacGraw in Love Story, etc.), I think our cultural representations of love really fuck us up. We hold up the often unattainable ideal—the proverbial boombox playing Peter Gabriel—at the expense of the far more likely and far more complicated reality that if we are lucky enough to fall in love, and make it last, we will not always feel good, or happy, or complete most of the time. That’s hard to sit with but I think it’s important. It doesn’t mean that we don’t get to feel joy or excitement ever again. It doesn’t mean we don’t deeply love our partners, even if we sometimes don’t like them. It means we are doing the hard work of being in a relationship with another messy, lovely, impossible, unknowable human being. On top of dealing with our own shit, which is truly terrifying.

Now that I think of it, maybe the best romantic comedy primer for real love is the ending of Bringing Up Baby, when Cary Grant spends years painstakingly reconstructing a dinosaur skeleton only to have Katharine Hepburn send it toppling to the ground because of her annoying joie de vivre. The plot summary on Wikipedia concludes: “David, resigning himself to a future of chaos, embraces Susan.” Also there’s the leopard on the loose. But that’s a metaphor for another day.